|

|

|

|

1) Iwao

Akiyama

Owls are

Iwao’s specialty and since the 1960s he has made more than two hundred

owl prints. Most of these prints were vertically oriented and showed a

single owl unaccompanied by any other objects, as in print 140. His style

is deliberately amateurish which makes it difficult to identify the

species of owl depicted. The owl’s body was always colored black and its

eyes red. Sometimes a hint of other colors was added, as in this print.

To complement the rough, unfinished look of the picture’s bird subject he

used rough, handmade paper which contained fragments of tree bark. Iwao’s

choice of paper, style and woodblock printing were influenced by the

Japanese Folk Art movementa which promoted the continued use

of traditional Japanese printmaking practices.

a

Blakemore (1975)

|

|

140

Owl (Family Strigidae) by Iwao Akiyama, 250 mm x 300 mm, woodblock print

entitled winter wind

|

|

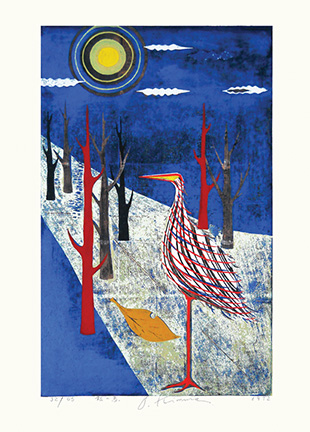

(2) Yoshiharu Kimura

During the

past fifty years Yoshiharu has made more than one hundred and seventy

bird prints. His bird subjects were typically large birds such as the

crane in print 141. Neither the bird nor other objects in his prints were

easily identified because he simplified their shapes and colored them

with a mixture of colors which were not true-to-life. In this print the

crane had no eye and only one foot and trees had few branches and no

leaves. The sun was multicolored instead of simply yellow and the ground

was grey and blue instead of brown. The combination of false color, novel

shapes and complex picture composition made each of his woodblock prints

both visually stimulating and highly entertaining.

|

|

141

Crane (Grus sp.) by Yoshiharu Kimura, 525 mm x 710 mm, woodblock

print entitled silver bird

|

|

(3) Atsushi

Uemura

Atsushi is

a painter who also designed more than one hundred and fifty lithographic

bird printsa. Small birds such as the great tit in print 142

were his favorite subjects. Their shapes and colors were drawn very

accurately making identification easy. To focus attention on the

picture’s bird subjects few other objects were included and a single,

contrasting color was chosen for the background. Here warm colors (i.e.,

orange background plus red leaves and fruits) were contrasted with the

birds’ cooler colors (i.e., greyish tail and wings plus black head).

a

Most painters chose lithography presumably because the act of drawing a

design on stone was most similar to painting a design on paper. Other

printmaking techniques required additional technical skill (i.e., carving

wood, cutting into a metal plate, making a stencil or screen, or learning

to use a computer drawing program).

|

|

|

142

Great tit (Parus major) by Atsushi Uemura, 660 mm x 540 mm,

lithograph entitled autumn field

|

|

(4)

Kōji Ikuta

Kōji

has made more than one hundred bird prints during the past twenty-five

years. Black-and-white mezzotint (i.e., intaglio) prints of owls are his

specialty. His choice of mezzotint to depict owls is perhaps not

surprising because it provides the dark background appropriate for a bird

of the night. Kōji also took advantage of the mezzotint’s ability to

show even slight differences in feather tone to depict owls with near

photographic accuracy, as in print 143. The Blakiston’s fish owl in the

foreground is one of the largest and rarest of Japanese owls while the

scops owl in the background is one of the smallest and most common. Most

other prints featured only a single owl species and were oriented

vertically. Picture composition was always simple with only the moon and

(or) a plant also included in the picture.

|

|

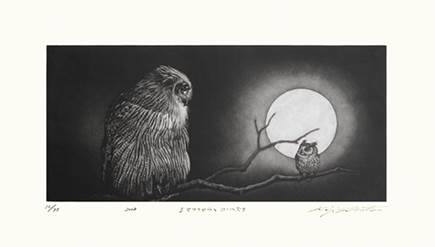

|

143

Blakiston’s fish owl (Ketupa blakistoni) and scops owl (Otus

scops) by Kōji Ikuta, 460 mm x 260 mm, intaglio print entitled

Blakiston’s fish owl and scops owl

|

|

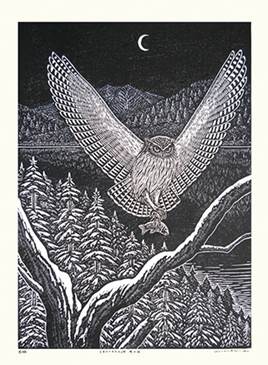

(5)

Keisaburō Tejima

During the

past thirty years Keisaburō has made more than eighty woodblock

prints of birdsa. He focused on birds native to his home in

northern Japan and especially on the endangered Blakiston’s fish owl. In

print 144 he showed this owl returning to its perch in a tree after a

successful fishing trip. It is one of the world’s largest owls and

Keisaburō did not exaggerate the length of its outstretched wings by

much. He chose to depict it in only black and white in this night scene

but in most other prints birds were drawn in full color. This bird only

inhabits coniferous forests near water as shown in the background. The

appearance of coniferous forest in a Japanese bird print is unusual

because most artists focused on birds of the heavily populated southern

part of Japan where other types of habitat are more common.

a

Keisaburō also designed books about birds for children, some of

which have been translated into English for sale outside Japan (e.g.

Tejima, 1984).

|

|

144

Blakiston’s fish owl (Ketupa blakistoni) by Keisaburō Tejima,

450 mm x 610 mm, woodblock print entitled owl’s lake – winter moon

|

|

(6) Keiko

Minami

From the

1950s to the 1990s Keiko made more than eighty bird prints. She was a

pioneer in several ways. First, she was one of the first Japanese femalesa

to make bird prints and second, she used the intaglio method of

printmakingb instead of traditional Japanese woodblock

printing. Print 145 is a typical example of her workc.

Mythical birds and plants were often paired to create simple scenes of a

fairy-tale world. Her childlike style of drawing shapes and using color

was novel for the time and it helped to make her prints popular with

patrons of modern bird art both in the west and in Japan.

a No ukiyo-e or shin hanga bird printmakers were female versus about 14% of

gendai bird printmakers in the sample of prints examined.

b Keiko learned intaglio techniques while living in France (Kawakita,

1967).

c

See Minami (2006) for additional examples of her bird prints.

|

|

|

145

Unidentified bird by Keiko Minami, 570 mm x 380 mm, intaglio print

|

|

(7) Tomoko

Kyūki

Tomoko is a

female printmaker who has made more than seventy bird prints in the last

ten yearsa. Her designs are modern but her printmaking

technique is traditional. In print 146 the simplified, semi-transparent

shapes of the bird and trees are very modern but the black outline and

evenly applied color is typical of traditional Japanese woodblock prints.

The vertical format and relatively small size of this print are also more

in keeping with traditional Japanese bird prints than with modern large,

horizontally-oriented bird prints (e.g., print 145). However, most of the

birds she selected for depiction, including this common cuckoo, were not

chosen by traditional Japanese bird printmakers. Her unusual choices

suggest that she is a birdwatcher as well as a bird artist.

a

other examples of Tomoko’s bird prints are shown on her website http://kyuki.fool.jp/

|

|

146

Common cuckoo (Cuculus canorus) by Tomoko Kyūki, 100 mm x 150

mm, woodblock print entitled bird’s time - common cuckoo

|

|

(8)

Umetarō Azechi

Umetarō

made more than seventy woodblock prints of birds during the last half of

the twentieth century. The bird was a source of astonishment and pleasure

to Umetarō and it appeared in his work as a symbolic statement of

lifea. Umetarō’s favorite bird was the rock ptarmigan

which he would have encountered while climbing mountains during his free

time. In his depictions of mountains and birds (e.g., print 147) he

attempted to capture their essence and eliminated what he considered to

be unnecessary detail. The resulting simplicity of shape, color and

composition may cause his work to be thought of as amateurish by viewers

who are either unfamiliar or unsympathetic with his style of art.

a

Petit (1973)

|

|

147

Rock ptarmigan (Lagopus muta) by Uemtarō Azechi, 125 mm x 115

mm, woodblock print

|

|

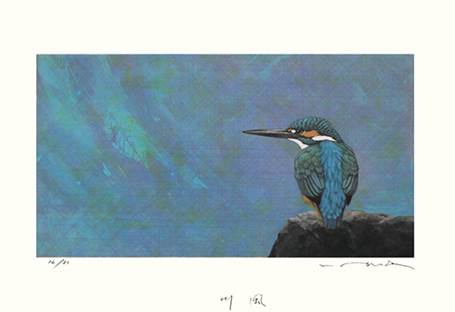

(9) Tadashi

Ikai

Tadashi

started to make mezzotint prints in the 1970s and since then he has made

more than fifty bird prints. His three favorite bird subjects are the

common kingfisher shown here in print 148, the Japanese white-eye (print

127) and owls (print 126). He drew the shapes of these birds very

accurately and used graded, accurate colors to make them appear very

lifelike. The bird always appeared in the foreground against an

indistinct background of mixed colors and shapes. Here a single leaf was

the only identifiable shape in the background. This combination of an

indistinct background and a distinct foreground object created the

illusion of a three-dimensional picture which is unusual for modern Japanese

bird prints.

|

|

|

148

Common kingfisher (Alcedo atthis) by Tadashi Ikai, 440 mm x 300

mm, intaglio print entitled river breeze

|

|

(10)

Kunihiro Amano

Kunihiro is

one of the post-World War II generation of Japanese artists who combined

traditional Japanese woodblock printmaking techniques with modern,

western artistic style. The word abstract best describes the birds that

appear in his more than fifty bird prints. In print 149 the long neck of

the bird in the foreground and the long wings of the bird in the

background suggest that they are cranes. However, their coloring made

them look like they had either been tattooed or were wearing colorful

Japanese kimonos. Kunihiro’s novel depiction of birds never fails to

stimulate the viewer’s imagination which is one reason why some people

find abstract art so attractive. The composition of his pictures was

typically simple and balanced as in this print. Kunihiro often drew

pictures with similar compositions which were issued as a series (e.g.

this morning series).

|

|

149

Unidentified bird by Kunihiro Amano, 170 mm x 230 mm, woodblock print

entitled morning 31

|

|

(11)

Shirō Takagi

Shirō

received art instruction from Kunihiro Amanoa, described

above, so it is not surprising that their bird prints are similar in some

ways. For example, Shirō also tattooed his cranes with unusual

patches of color in print 150. This print also shared the simple, balanced

composition of print 149. Shirō simplified the shapes of his bird

subjects but not to the extent evident in Kunihiro’s prints. The word

semi-abstract best describes Shirō’s prints. He also designed more

than fifty bird prints but he chose a wider range of bird species as

subjects for these prints. Cranes, peafowl and doves were his favorite

subjects and each appeared in more than one print with a similar

composition. However, unlike Kunihiro, prints with a similar composition they

were not issued as a numbered series.

a

Merritt and Yamada (1992)

|

|

150

Red-crowned crane (Grus japonensis) by Shirō Takagi, 200 mm x

230 mm, woodblock print

|

|

(12)

Ay-Ō (Takao) Iijima

Ay- Ō

started to make screenprints using the Pop Art style after he moved to

the United States in the 1960sa. More than fifty of these

prints featured birds. Print 151 is a typical example. He simplified

actual bird shape and applied color in a rainbow fashion which made it

difficult to identify the species depicted. Picture composition was

always simple and a single bird was often the only object shown. Many

pictures had a patterned background which was also colored in rainbow

fashion. This novel use of a rainbow of colors is a unique feature of his

work and for this reason he was nicknamed rainbow man.

a Sakai (1992)

|

|

|

151

Unidentified bird by Ay-Ō, 170 mm x 120 mm, screenprint entitled

sings-A

|

|

(13) Masao

Ohba

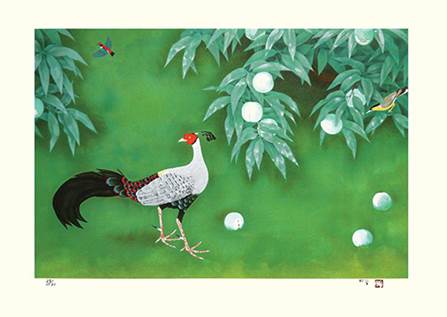

Masao used

an unusual screenprinting techniquea to make more than fifty

bird prints during the late twentieth century. Instead of making the

screen from mesh fabric he used porous paper. Ink was forced through a

series of these paper screens to create a complex, multicolored design

within the outline of a bird, which was typically a domestic fowl (print

152) or owl. Masao’s use of color was creative rather than realistic. He

also simplified the bird’s shape using a combination of smooth curves and

straight lines. The hard edge of the bird’s outline was then softened by

adding a speckled border. The background was left blank in most bird

prints presumably to allow the viewer to focus on the complexities of the

bird’s shape and surface.

a

See Johnson and Hilton (1980) for a more complete description of this

technique.

|

|

|

152

Domestic fowl (Gallus gallus) by Masao Ohba, 150 mm x 90 mm,

screenprint entitled cock

|

|

(14)

Masahiko Saga

Masahiko is

a digital printmaker and illustrator who has made more than fifty bird

prints during the past decadea. His choice of bird subject was

influenced by the work of the innovative ukiyo-e artist Jakuchū

Itō who specialized in painting domestic fowl. Masahiko’s depiction

of domestic fowl is equally novel, as shown in print 153. He colored them

entirely blue and gave them a flamboyant tail. Fowl were typically paired

with flowers, similar to ukiyo-e bird-and-flower pictures. The picture’s

vertical format and absence of a white picture border were also similar to

most ukiyo-e bird prints.

a

More examples of his bird prints are shown on his website http://magicstrange.com/

|

|

153

Domestic fowl (Gallus gallus) by Masahiko Saga, 300 mm x 420 mm,

digital print

|

|

(15)

Ryūji Kawano

Ryūji

is an illustrator and digital printmaker whose artwork includes more than

forty bird prints. He chose a range of bird species as subjects for these

prints and drew each bird in a creative way. The plump caricature of a

red-crowned crane in print 154 is a good example. Both the bird and other

objects that were included in a picture looked crisp, clean and three

dimensional because Ryūji first outlined their shapes using a thin

black line then filled the shape with strongly graded color. Birds were

typically shown in an idealized Japanese landscape scene with rugged

mountains, clear water and a deep blue sky. Such scenes would be

especially pleasing to Japanese viewers.

|

|

154

Red-crowned crane (Grus japonensis) by Ryūji Kawano, 300 mm x

420 mm, digital print

|

|

(16) Masaki

Shibuya

Masaki has

made more than forty black-and-white bird prints using three different

printing methods; namely, wood engraving, woodblock and intaglio. Print

155a is a one of his wood engraved prints. One of the most notable

features of these wood engraved prints is the small size of the picture

portion of the print. It is only 30 mm in diameter in print 155a. To

fully appreciate the fine details of these small pictures requires either

a magnifying glass or an enlarged version such as print 155b. Despite

their small size many pictures included both a bird and a complete

landscape in the background. Masaki’s favorite bird subjects were owls

but no attempt was made to copy the external features of real species.

Instead, each was drawn in a highly creative way with no two alike. This

novelty makes his prints very entertaining.

|

|

|

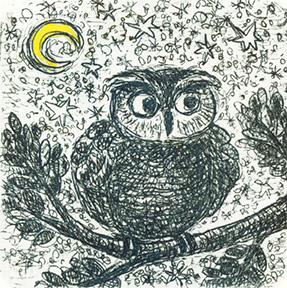

155a

Owl (Family Strigidae) by Masaki Shibuya, 120 mm x 135 mm, wood engraved

print entitled under the stars

|

|

|

|

155b

Enlargement of the picture portion of print 155a

|

|

(17) Makiko

Hattori

Makiko is

an intaglio printmaker whose print production to date includes more than

forty bird prints. Like Masaki Shibuya above, the picture

portion of most of her prints is very small and a visual aid may be

required to fully appreciate its details. Print 156a is an example of one

of these small prints and an enlargement of its picture portion is

provided in print 156b. Her favorite bird subject is the owl but also

like Masaki Shibuya above her depiction of birds is best described as

creative. The combination of a short, round body and larger-than-life

dark, round eyes made the owl in print 156a look like a cute, stuffed toy

instead of a real-life killer of small animals and birds. The inclusion

of baby birds in other prints (e.g., print 100) reinforced the illusion

of cuteness.

|

|

|

156a

Owl (Family Strigidae) by Makiko Hattori, 130 mm x 130 mm, intaglio print

entitled starry sky (blue)

|

|

|

|

156b

Enlargement of the picture portion of print 156a

|

|

(18) Shūji

Wakō

During the past thirty

years Shūji has made lithographic prints featuring objects

associated with traditional Japanese culture. An origamia

crane appeared in more than forty of these prints. Print 157 is one

example. The crane was typically accompanied by brightly colored objects

which were drawn in a photo-realistic way and arranged in such a way that

they appeared to be floating in center of a vertically-oriented picture.

The picture’s solid black (or blue) background enhanced this optical

illusion. Shūji’s objective was to express his inner sense of

Japanese tradition through modern eyes.

a origami is the Japanese name for the

art of folding paper to make an object.

|

|

157 Crane (Grus sp.) by Shūji

Wakō, 385 mm x 565 mm , lithograph entitled folded crane - spool

|

|

(19)

Tōshi Yoshida

Tōshi

made more than forty bird prints during a long career which started in

the 1930s and ended with his death in 1995a. Many of these

bird prints were published during the 1970s, including print 158. Birds

and other objects in the picture were drawn realistically, reflecting the

training he received from his artist father who used the shin hanga

style. Birds were typically not the largest object in his pictures.

Instead, they were part of a landscape scene appropriate for the species

depicted. This coastal scene of cormorants resting on a rocky island is a

good example. Tōshi depicted birds from a greater range of habitats

and continents, including Antarctica (print 98), than any other Japanese

bird artist. He and his father were world travelers which provided both

the opportunity and experience needed to draw foreign birds and their

habitats accurately.

a

See Skibbe (1996) for more information about Tōshi plus other

examples of his prints.

|

|

158

Cormorant (Phalacrocorax sp.) by Tōshi Yoshida, 400 mm x 545

mm, woodblock print entitled cormorant island

|

|

(20)

Shōkō Uemura

Shōkō

was a twentieth century painter who also made both woodblock prints and

lithographic prints during his long career. Print 159 is one of his more

than forty bird prints. He chose a wide range of brightly-colored bird

species for depiction many of which appeared nowhere else in gendai bird

prints (e.g., the three species in print 159). Birds were typically

paired with flowers or fruits which added extra color. To highlight these

colorful bird and plant subjects he usually left the background empty and

filled it with a muted color. Plants and birds were drawn with sufficient

accuracy to allow them to be identified by the viewer but they were not

true-to-life (e.g., robin’s wings are too large and pheasant’s head is too

small in print 159). Shōkō taught his style of bird printmaking

to his son Atsushi whose prints were described above (i.e., notable

gendai artist 3).

|

|

|

159

Siamese fireback pheasant (Lophura diardi), yellow-breasted magpie

(Cissa hypoleuca) and Ryūkyū robin (Erithacus

komadori) by Shōkō Uemura, 630 mm x 455 mm, lithograph

entitled pheasant beneath the trees

|

|

(21)

Shūzō Ikeda

During the

last half of the twentieth century Shūzō made more than forty

woodblock prints which showed birds accompanied by children (e.g., print

160). Depicting the fascination of children with nature was one of the

major themes of Shūzō’s artb. In print 160, as in

most others, the bird’s shape and color were simplified to be compatible

with those of the child. Consequently, the bird’s characteristics rarely

matched those of an actual bird. This mismatch would likely be

unimportant to viewers for whom the picture triggered a fond memory of a

similar childhood encounter with a bird.

b

Blakemore (1975)

|

|

160

Unidentified bird by Shūzō Ikeda, 140 mm x 125 mm, woodblock

print

|

|

(22) Kazu

Wakita

Kazu was a

modernist painter who also made more than forty lithographs showing birds.

He depicted the world of dreams in which neither the bird nor any of the

other objects appearing in a picture were true-to-life. Birds were

usually outlined in black and colored to match the background color as in

print 161. Color was applied haphazardly which created a patchwork

effect. To help unify this patchwork Kazu typically used only different

shades of a single, dominant color (e.g. orange in print 161). Despite

this color unity the patchwork of colors and shapes required careful

study for the major features of the picture’s design to become apparent.

The dual challenge of recognizing and interpreting these major features

may limit to the appeal of Kazu’s artwork to those who enjoy puzzles.

|

|

|

161

Unidentified bird by Kazu Wakita, 480 mm x 380 mm, lithograph

|

|

(23)

Rokushū Mizufune

Rokushū

was a sculptor and woodblock printmaker active in the 1960s and 1970s.

During this period he made more than forty bird prints. His favorite bird

subject was the gull which he saw during his walks on the beach near his

seaside homea. The gull in print 162 is hardly recognizable

because neither its shape nor color is true-to-life. Rokushū created

only an abstract version of the bird he depicted using a combination of

lines, circles and others shapes. Any additional objects appearing in the

picture were similarly abstracted and they were often even more difficult

to identify (e.g., objects at the bottom of print 162). Color was applied

in layers using thick, opaque pigment which made the print look and feel

more like an oil paintingb. Superimposed layers were purposely

mismatched to give each object rough edges. Rokushū’s intent was to

make these objects look worn, similar to those he saw washed up on the

beach.

a Merritt (1990)

b

Johnson and Hilton (1980)

|

|

162

Gull (Larus sp.) by Rokushū Mizufune, 225 mm x 250 mm,

woodblock print entitled seagull

|

|

(24)

Tomikichirō Tokuriki

Tomikichirō

was a versatile artist who made accurately drawn landscape prints for the

souvenir market and more creative prints for his own pleasure. His more

than forty woodblock prints of birds fall into the creative category.

Birds were drawn with streamlined shapes or with simplified colors, as in

print 163. A variety of popular bird species were chosen for depiction,

not just owls. Some birds were shown sitting quietly on a tree branch, as

in this picture, while others were shown swimming or in flight.

|

|

|

163 Ural

owl (Strix uralensis) by Tomikichirō Tokuriki, 540 mm x 410

mm, woodblock print

|

|

(25) Tamami

Shima

Tamami was

the first female Japanese artist to make a woodblock-printed bird print.

From the 1960s onwards she made more than forty bird prints. These bird

prints are best described as big and bold. Big birds such as peafowl,

cranes or geese were chosen most often for depiction and their bodies

were elongated (e.g. neck of peafowl in print 164) to make them look even

larger. Print size was also big which made the birds look larger still.

Tamami often replaced dull, naturally-occurring colors with bolder ones.

For example, the back and tail of the peafowl in print 162 were colored

red instead of their true colors. Boldly colored backgrounds also

appeared in many of her prints. Here the woodblock’s natural grain was

first enhanced by carving a set of abstract shapes and then contrasting shades

of red and blue were used to color these shapes.

|

|

164

Indian peafowl (Pavo cristatus) by Tamami Shima, 190 mm x 280 mm,

woodblock print entitled “with”

|

|

(26) Kaoru

Kawano

Kaoru made

more than forty woodblock prints of birds during the 1950s and early

1960s. He used a set of intersecting, curvilinear shapes to depict his

bird subject in a highly creative way (e.g., print 165). His use of color

was also creative rather than realistic. Birds were often oriented in an

unexpected way, for example this horizontal owl. Owls and cranes were

Kaoru’s favorite subjects and they were typically unaccompanied as in

print 165.

|

|

|

165

Owl (Family Strigidae) by Kaoru Kawano, 415 mm x 270 mm, woodblock print

|

|

(27)

Mitsuru Nagashima

During the

past twenty-five years Mitsuru has made more than thirty bird printsa.

Most were black-and-white intaglio prints like print 166. Even without

full color the birds in his prints were easily identified. Their shapes

were drawn accurately, their characteristic behavior was depicted and

their habitat was shown in the background. Mitsuru clearly spent time

watching birds closely. His attention to detail is especially noteworthy.

For example, in print 166 even ripples in the water caused by the bird’s

movement were included.

a

More examples of his bird prints are shown on his website http://mnagashima.webcrow.jp/w-art.html

|

|

166

Black-winged stilt (Himantopus himantopus) by Mitsuru Nagashima,

315 mm x 415 mm, intaglio print entitled black-winged stilt

|

|

(28) Shiko

Munakata

During the

1950s and 1960s Shiko made more than forty bird prints. Words such as

dynamic, spontaneous and powerful are often useda to describe

his woodblock prints. He worked rapidly using short chisel strokes to

draw angularly-shaped birds and plants. Powerful birds such as the hawk

in print 167 were depicted most often and they were shown in an active

position (e.g., wings raised in print 167). Shiko mostly used single

color printing (i.e., black) apparently because he was too impatient to

re-carve portions of a design for additional colorsb. Shiko

was a member of the Japanese Folk Art Movement which promoted this

unsophisticated style of art.

a

Blakemore (1975), Munsterberg (1982)

b

Merritt (1990)

|

|

|

167

Hawk (Family Acciptridae) by Shiko Munakata, 345 mm x 305 mm, woodblock

print

|

|

(29)

Hidetaka Yamanaka

During the

past fifteen years Hidetaka has made more than thirty bird printsa.

Small birds such as the Japanese white-eye in print 168 are his favorite

bird subjects. Their shapes were drawn very accurately but his use of a

limited number of muted colors for each print meant that their color

scheme was not always true-to-life. In print 168 additional shades of

green and yellow were needed to show the white-eye’s contrasting throat

and back colors evident in print 172 below. The crisp, clean look of the

white-eye in print 172 also differs from the fuzzier version drawn here

by Hidetaka. This difference results from his use of the mezzotint

printing technique which is better suited to showing gradual rather than

abrupt change in color.

a

More examples of his bird prints are shown on his website http://hya.main.jp/gallery_1.html

|

|

168 Japanese

white-eye (Zosterops japonicus) by Hidetaka Yamanaka, 280 mm x 275

mm, intaglio print entitled suntrap

|

|

(30) Fumio

Fujita

Fumio made

his first woodblock prints in the early 1960s. Since then he has

published more than thirty bird prints. In each of these prints the shape

and color of the bird was reduced to a minimum. For example in print 169

he used a set of short straight lines and no color to draw the silhouette

of a bird in flight. None of the birds in his prints are identifiable.

Other objects that appeared in the background of his bird prints were

also difficult to identify because they were drawn using the same

minimalist style. This print’s title (i.e., to the sky) suggests that the

horizontal shapes are clouds. The vertical lines are more puzzling. Do

they represent falling rain? The challenge of identifying objects in

Fumio’s art is part of its appeal.

|

|

169 Unidentified

bird by Fumio Fujita, 140 mm x 160 mm, woodblock print entitled to the

sky

|

|

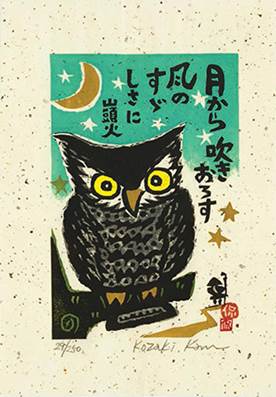

(31) Kan

Kozaki

During the

past thirty years Kan has made more than thirty entertaining bird prints.

The picture’s bird subject is almost always a small owl as in print 170.

Kan used his imagination when drawing these owls and no two were exactly

alike. Most owls were colored using only shades of grey for the body,

bright yellow for the eyes and brown for the beak and feet, as in this

print. Birds were typically placed in the foreground with the moon and a

starry sky in the background. A lighthearted verse also appeared in the

background of each printa. Kan is one of only a few gendai

artists who include a verse of text within the picture area. Other

artists titled a picture with a few words written in the bottom picture

border instead. Kan’s use of rough, handmade paper for his woodblock

prints was also unusual.

a

Verses were written by Santoka Tanaeda. The verse on this print says “the

wind blowing down from the moon is cool”.

|

|

170

Owl (Family Strigidae) by Kan Kozaki, 220 mm x 320 mm, woodblock print

|

|

(32) Kōichi

Sakamoto

Kōichi

started to make mezzotint prints in the mid-1950s. Since then he has made

more than thirty bird prints. His favorite bird subjects are owls (print

171) and doves (print 114). He made them look very sleek by elongating

their bodies and smoothing the edges of their body parts. Edges were also

indistinct, as in all mezzotint prints, which contributed to the birds’

streamlined look. He also made birds look very elegant by simplifying

their natural, complex color patterns. Here the owl’s natural colors are

reduced to shades of grey. The picture composition of many of

Kōichi’s bird prints is more surreal than real. For example, the

scops owl depicted here could only be seen standing in a grassy field in

the fantasy world of dreams.

|

|

|

171

Scops owl (Otus sp.) by Kōichi Sakamoto, 185 mm x 150 mm,

intaglio print entitled catbird No. 2

|

|

(33) Shizuo

Ashikaga

Shizuo used

woodblock printing to make more than twenty bird prints. He focused on

small, native Japanese birds such as the Japanese white-eye in print 172.

His style was more similar to that of shin hanga artists than to the

style of most other gendai artists. External features of birds were drawn

accurately and moderately graded color was applied to reproduce the

bird’s actual color scheme. Birds were typically paired with brightly

colored flowers or fruits which had a symbolic associationa in

Japan. Birds and plants were the only objects depicted and the empty

background was colored with the soft pastel colors used by many shin

hanga artists for their bird-and-flower prints.

a

The heavenly bamboo (Nandina domestica) in print 172 is associated

with longevity and good fortune.

|

|

172 Japanese

white-eye (Zosterops japonicus) by Shizuo Ashikaga, 190 mm x 280

mm, woodblock print

|

|

(34) Yoshio

Kanamori

Yoshio made

his first woodblock prints in the 1950s and since then he has made more

than twenty bird prints. He chose a wide range of popular species for

depiction including the green pheasant in print 173. Birds were always

outlined in black and colored creatively instead of accurately. Their

angular shape showed the influence of Shiko Munakata (e.g., print 167)

with whom Yoshio studied initially. Yoshio’s trademark was the silver-colored

mountain lake and sharp peaks which appeared in the background of each

print.

|

|

|

173

Green pheasant (Phasianus versicolor) by Yoshio Kanamori, 360 mm x

230 mm, woodblock print entitled mountain lake bird and maple

|

|

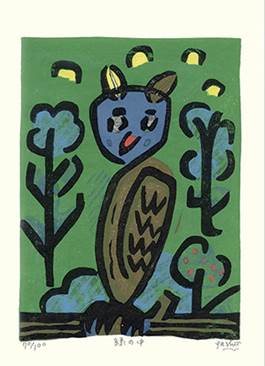

(35)

Gashū Fukami

Gashū

made his first woodblock prints in the 1970s. To date he has made more

than twenty bird prints. Birds were drawn in a modern, semi-abstract way.

The bird in print 174 was clearly one of the eared owls but its shape was

too distorted to know whether it was modeled on a scops owl or Eurasian

eagle-owl. Its color scheme was also creative rather than accurate. Birds

and other objects in a picture were drawn using the traditional

outline-and-fill method employed by woodblock printmakers. In this print

objects were outlined in black and filled with other colors. Color was

applied evenly across the surface of most objects which made the picture look

two-dimensional. Plants and either the moon or sun typically accompanied

a single bird in Gashū’s pictures. Owls were only one of the many

different bird species he chose to depict.

|

|

174

Owl (Family Strigidae) by Gashū Fukami, 230 mm x 310 mm, woodblock

print entitled surrounded in green

|

|

(36)

Masahiro Tabuki

Masahiro is

an illustrator and digital printmakera who specializes in bird

art. Since 1995 he has published more than twenty digital bird printsb.

A wide range of native Japanese birds were depicted in these prints and

each bird was drawn with extreme accuracy. The near-photographic likeness

of the common kingfisher in print 163 is a typical example. Elements of

the bird’s habitat were also included in the picture but they were drawn

with varying degrees of accuracy. For example, in print 163 the cattail

plant (Typha latifolia) in the foreground was very accurate while

other objects in the background were indistinct. The contrasting accuracy

of background and foreground objects makes the picture look

three-dimensional.

a

Illustrators are the only Japanese artists to embrace digital printmaking

to date.

b

More examples of his bird art are shown on his website http://www.tabuki-art.com

|

|

175

Common kingfisher (Alcedo atthis) by Masahiro Tabuki, 280 mm x 275

mm, digital print entitled gentle breeze

|

|

(37)

Shirō Kasamatsu

Between the

mid-1950s and early 1970s Shirō published more than twenty bird

prints. He used traditional Japanese woodblock printing but his designs

were often very creative. For example, in print 176 the left side of the

picture shows an owl as it would appear during the day (i.e., sleeping)

while the right side of the picture shows the owl at night with its eye

open. His designs were fairly simple with the bird(s) centrally placed.

The remainder of the picture was either left empty or filled with a

landscape element such as the large plant in this print. The shapes and

colors of all objects were typically simplified to complement the simple

design. The Ural owl shown in this print appeared often in gendai bird

prints but unlike many other gendai bird artists Shirō was not an

owl specialist. Instead he drew an impressive range of native and exotic

speciesa.

a

See Grund (2001) for pictures of all Shirō’s bird prints.

|

|

176

Ural owl (Strix uralensis) by Shirō Kasamatsu, 285 mm x 405

mm, woodblock print entitled owl

|

|

(38)

Jun’ichirō Sekino

Jun’ichirō

used woodblock printing to make more than twenty bird prints between the

mid-1950s and mid-1980s. The word diverse best characterizes his artwork.

While his favorite bird subjects were large birds such as owls and

domestic fowl, he also drew smaller birds, both native and exotic. These

birds were drawn with varying degrees of simplification of form. Print

177 is one of his most abstract depictions of a bird. According to the

print’s title the bird was an owl but only the bird’s two

forward-pointing eyes matched an owl’s true form. Picture composition

ranged from very complex, for example the abstract forest included in the

background of this print, to very simple with birds as the only objects

depicted. Jun’ichirō’s eclectic art provides something for everyone.

|

|

177a

Unidentified owl (Family Strigidae) by Jun’ichirō Sekino, 685 mm x

505 mm, woodblock entitled forest owl

|

177b

Enlargement of the bird in print 180a

|

|

(39)

Kōtarō Yoshioka

Kōtarō

started to make screenprints in the 1990s and to date he has made more

than twenty bird prints. His choice of bird subject, style and format

make these prints suitable for home decoration, especially for a child’s

room. Familiar species were chosen for depiction, including owls (print

178) and domestic geese (print 110). He made these birds look cute and

friendly by simplifying their shapes and colors and, sometimes, by

showing them as a family group. He kept print size small and hundreds of

copies were made, presumably to make them affordable for even those on a

tight family budget. For these reasons Kōtarō’s bird prints

probably have a greater mass appeal than most gendai bird prints.

|

|

|

178

Owl (Family Strigidae) by Kōtarō Yoshioka, 250 mm x 200 mm,

screenprint entitled road to happiness

|

|

(40) Yukio

Katsuda

Since the

mid-1960s Yukio has published more than twenty different prints of the

same bird, the Eurasian eagle-owl. In these prints the owl

was most often shown sitting in its daytime roost where it was partly hidden

from view by plant leaves. Print 179 is one example. The most unique

feature of these prints is their color. Yukio used screenprinting to

apply small dots of ink across the picture’s surface. This process was

repeated many times using different colors to create the shapes of

objects included in the picture. These objects had indistinct edges and a

speckled or mottled surface which made them look three dimensional.

Despite an object’s fuzzy coloring and indistinct edges it was relatively

easy for the viewer to identify it when viewed from a distance because

its overall shape was very accurate.

|

|

179

Eurasian eagle-owl (Bubo bubo) by Yukio Katsuda, 320 mm x 475 mm,

screenprint entitled No. 124

|

|

(41)

Shigeyuki Ōhashi

During the

past thirty years Shigeyuki has made more than twenty screenprints

showing birds in flight. These birds were typically backlit by the sun

which meant that their silhouetted shape and color were the only clues to

their identity. White shapes resembling gulls (e.g., print 180) were

drawn most often. Landscape objects were colored to reinforce the

illusion that the viewer was looking directly into the sun. Here the

color of water was strongly graded to suggest reflected light while the

islands were uniformly colored to suggest shadows. In Shigeyuki’s

pictures it is the absence of detail which makes them look realistic.

|

|

|

180

Gull (Larus sp.) by Shigeyuki Ōhashi, 375 mm x 280 mm,

screenprint entitled migration I

|

|

(42)

Kiyohiko Emoto

Kiyohiko

started to make woodblock prints in the 1980s. To date he has made more

than twenty prints featuring owls. Print 181 is a typical example. The

owl was placed centrally in an imaginary scene which typically included

some man-made objects. Both the owl and man-made objects were drawn in a

childlike way using only one color (i.e., black). Hand-made paper was

used to print the picture and the paper’s imperfections nicely complement

the picture’s naivety. Kiyohiko’s style and use of hand-made paper

reflect the initial stimulus for his work; namely, prints made by Iwao

Akiyama (i.e., notable gendai artist 1).

|

|

|

181

Scops owl (Otus sp.) by Kiyohiko Emoto, 310 mm x 185 mm, woodblock

print entitled round moon

|

|

(43)

Shigeki Kuroda

Shigeki

began making intaglio prints in the 1970s. Since then he has made more

than twenty bird prints. Like many intaglio printmakers, he drew both the

shape and plumage of birds very accurately but usually colored them only

in shades of gray. Print 182 is one example. The small size of this print

is also typical of intaglio bird prints. The bird subject of this print

(i.e., cormorant) was not often chosen by Japanese printmakers, perhaps

because it is not particularly attractive. Most of the birds depicted by

Shigeki were not often chosen by other artists, including the hummingbird

in print 115. His bird subject was typically shown close up with an

uncluttered background of water for aquatic birds or a flowering plant

for land birds.

|

|

|

182a

Cormorant (Phalacrocorax sp.) by Shigeki Kuroda, 140 mm x 205 mm,

intaglio print

182b

Enlargement of the picture portion of print 182a

|

|

(44) George

Ueda

George is a

contemporary printmaker who has made more than twenty bird screenprints

to date. His birds resemble cute cartoon characters with large heads and

small bodies (e.g., print 183). They typically appear in a group in his

pictures and he adds a title which implies interaction among group

members. Here the title is “ talk about …” which suggests that this trio

of flycatchers was busy catching up on the latest gossip. The combination

of a clever title and a novel bird shape make his prints entertaining.

George gave his prints a smooth, clean look by applying color uniformly

to objects drawn with sharp edges. The disadvantage of applying color

uniformly was that it made objects look two dimensional. Most other

artists who made bird screenprints applied color unevenly across the

surface of an object so George’s prints are unusual in this respect.

|

|

|

183 Narcissus

flycatcher (Ficedula narcissina) by George Ueda, 200 mm x 135 mm,

screenprint entitled “talk about …”

|

|

(45)

Hiromitsu Sakai

Hiromitsu

is a contemporary nature artist who was attracted to birds by the beauty

of their feather patternsa. Using digital technology he

attempts to capture the subtleties of color gradation within and between

feathers in his more than twenty digital bird prints. In print 184 he

combined shades of gray with a black background to create the illusion

that an otherwise all white little egret was side lit by the moon.

Choosing to depict the egret with its back to the viewer was also

creative. The normal practice was to show it from either the front or

side. The bird in Hiromitsu’s prints is typically unaccompanied by any

other objects, presumably because his primary interest is the bird rather

than its surroundings.

a

Sakai (2013)

|

|

184

Little egret (Egretta garzetta) by Hiromitsu Sakai, 295 mm x 425

mm, digital print

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|